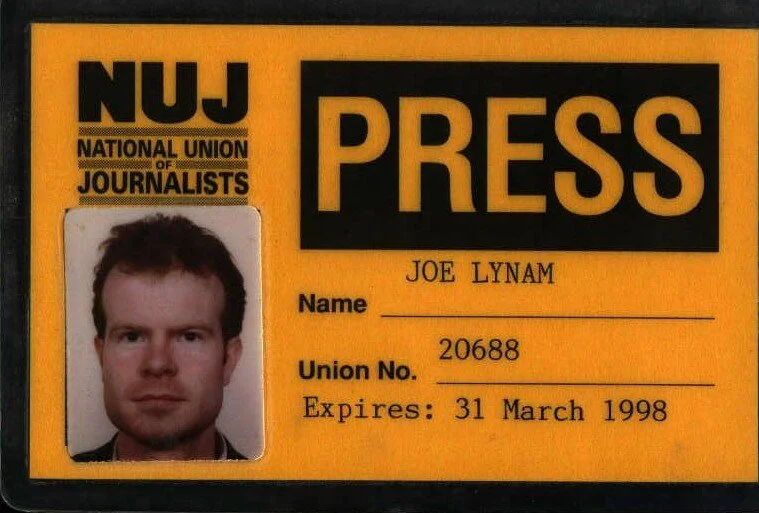

In early 2001 when I used to be a freelance technology journalist my luck was starting to run out. The Dot Com boom had turned into the Dot Com Bomb. Shares had collapsed to pretty much where they deserved to be: i.e. all-but worthlessness and newspapers and magazines were rapidly shedding Tech supplements and even articles because the advertising that drove them had evaporated. I had a mortgage and my sporadic income was starting to resemble a lesser spotted eagle. I even started contacting PR companies but they weren't interested in hiring me either because I had no experience of note to offer them.

Then one day, I was desperately trawling the media jobs section in The Guardian when I saw an advert from the BBC looking for a Broadcast Journalist based in London. At first my heart leaped at the prospect but then my head told it to sit down and put on the kettle.

No-one (according to my sensible, pragmatic alter ego) gets jobs in major organisations which are advertised in national or international papers. That job had probably already been assigned to someone in-house and the trade unions had insisted that it be advertised to make things seem above board and ‘kosher’.

But since I was looking at impecuniosity, I applied nonetheless. Three weeks later I was summoned for an interview at TV Centre in Shepherds Bush. That alone made my spirits levitate. When you've grown up watching programmes (Blue Peter and Top of the Pops etc) being broadcast from that very building, it has a place in your mind which can only be likened to magic or a broadcasting Narnia. So I booked my flight from Dublin and only informed my sister, who lived there, because I’d needed to ‘crash’ on her sofa bed before doing the interview. Under no circumstances would I inform my mother or even close friends. To fail publicly was the last thing I would do. Male pride is a very powerful thing.

Before travelling to London I paid for a course in ‘how to pass that job interview’. I’d scoff at such a thing nowadays but back then I knew that I didn't tend to come across well in interviews. Too confident, too chatty, over familiar, over talkative, ill prepared, tending to stray off the subject was just some of the feedback I got from previous would-be employers.

The course taught me to focus and ‘stick to the facts ma’am’.

I went to a greasy spoon near TV Centre on the day of the interview and learned off my talking points. When I was called into the ‘board’ as job interviews are known only within the BBC, I was shaking like a leaf. I did what I regarded as a dreadful interview. I admitted to the board that I didn't know many of the programmes that I would be working on because they simply weren't available in Ireland eg Breakfast TV, Wake up to Money and the Today programme. This was not strictly true but they couldn't prove otherwise. After all many Brits thought even in the early 21st century that Ireland barely had running water.

It was an utter disaster and I even resorted to telling them about my businesses in Germany, which had little relevance to broadcast journalism.

I flew home to Dublin and mentally wiped the whole process out of my head. I would not be back to the BBC ever again.

Then on Valentines Day 2001, I got a missed call from an unknown number while I was out covering a story for one of the few magazines who still paid me. When I dialled the voicemail, there was a very short message from one of the editors who had interviewed me a few weeks earlier.

‘Hello Joe, I’d like to offer you a job’.

The whole left side of my body fainted as I stood (staggered) in the lobby of a swanky Dublin hotel.

‘Could you call me back and confirm you’d like to accept it and we can get started without delay’.

I flopped into a nearby sofa. My world swirled around as I tried to digest the fact that a lifelong dream was about to come true. I had studied journalism and been presenting a show on a minor Irish radio channel and now I was being offered a job working in television with the best broadcaster du monde, after doing the worst interview in my life.

I wanted to call the editor back and get the offer in writing because bitter experience had taught me never to assume anything until it was written down. But I had two problems, my hands were shaking violently and I had no number for him because the BBC always call using ‘Unknown’ as the identifier.

So I had to compose myself - as the lobby blurred around me. My blood pressure was so intense that I could hear it flood through my ear lobes.

I called directory inquiries to get a number for the BBC switchboard. This was well before smartphones and mobile internet. I struggled to write down the number with my sudden onset Parkinson’s and then I had to grapple with the tiny keyboard of my Nokia 8310.

After 3 attempts I eventually got through to the man whose voice message would change my life forever. And although we quarrelled a lot in subsequent years as he held back my BBC career advancement, I would have married him at that moment.

After accepting his job offer of a 6 month contract, I asked him to confirm it by email. To his credit, he did so there and then on the phone to me. Once received, I asked him something that I’m sure he rarely gets upon offering people jobs:

‘Why did you give me the job?’ I inquired. ‘I did what I regarded as a poor interview with you.’

‘We saw a lot more than just what you did in journalism,’ he replied candidly, not hiding the fact that my ‘board’ had been rubbish. ‘We saw a life in business, a more mature candidate and someone who would add to the BBC.’

Millions might have argued the ‘mature’ bit of that sentence.

I started with the BBC on the 3rd of April 2001 and I’m still broadcasting for them 20 years later.

FIN

Why not take a listen to my latest Podcasts: Connected Investor, EUNICAST: Meet Visionary Europeans or Global News Podcast